This cross-post has originally been published on the ScholarLed blog.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.59350/2z69g-xbz37

Over the last few years, I have had the opportunity to closely follow the work of a variety of community- and scholar-led publishing initiatives, while also becoming more deeply involved with a few of them. Most notable for me here has been the work of the Radical Open Access Collective (ROAC), which provides a loose conceptual framework for not-for-profit presses, journals, and other communities that subscribe to a progressive notion of open access with a focus on creative experimentation, while many of them also engage in thorough critiques of mainstream open access against the backdrop of the prevalent neoliberal Higher Education system. As Adema and Moore (2017) write, the ROAC “highlights the importance of making publishing more diverse, equitable, and open to change, where it wants to ensure that new and underrepresented cultures of knowledge are able to have a voice.”

The other collective that I’ve been excited to work with – through the recently-ended Community-Led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs (COPIM) project – is the ScholarLed consortium. ScholarLed comprises a group of independent and scholar-led Open Access book publishers who joined forces in a collaborative endeavour to share (often tacit) knowledge, experiences, and book publishing practices, while also collaborating on shared goals under the emerging principle of what now has become known as ‘scaling small’ (see e.g. Adema & Moore, 2021).

With my own background in the Humanities and having previously worked with various projects in Open Publishing and Open Scholarship more broadly, I have been drawn to the work of both groups right from their inception in 2015 and 2018, respectively. Correspondingly, and over the years, I have seen notions of community- and scholar-led publishing emerge in a variety of contexts, and, as it turns out, with sometimes surprisingly divergent connotations.

Intrigued by this and accompanied by ongoing engagement with the ever-growing body of research on the topic of independent, scholar-led publishing, I have for a couple of years tried to make sense of how terms such as community-led and scholar-led are being applied in different contexts to describe particular sets of approaches to scholarly publishing.

In case you are interested in learning more about this always developing field yourself, make sure to check out this topical Zotero collection, which has lots of pointers to e. g. the foundational research by ROAC members Janneke Adema and Sam Moore. To provide a set of examples that may illustrate the multitude of scholar-led initiatives that exist in the Humanities and Social Sciences, the below interactive timeline might also be of interest.

What I continue to be fascinated by is the daily usage of a whole set of terms in scholarly communications circles that relate to this type of publishing activity… and how much the corresponding underlying interpretations still seem to differ, although the terms themselves – including “scholar-led”, “academic-led”, “library-led”, “community-led”, “community-driven”, etc. – often tend to be used quasi-synonymously.

Unfortunately, it turns out that this kind of conceptual fuzziness can become problematic when we account for the different contexts that each of these groups is operating in, and the correspondingly different motivations and politics that they might bring to the larger metaphorical table of open access publishing.

Take, for example, the difference of realities that library-led and scholar-led publishing initiatives are working in: while the former, i.e. library-led initiatives, might well be able to rely on backing from their home institution when it comes to questions of e.g. access to financial, legal, infrastructural and/or staffing support, the latter, i.e. scholar-led initiatives, are often looking for more independence and direct, self-determined agency in how to define their publishing communities and the – often more experimental – practices and corresponding theoretical underpinnings of their activities, and have thus have deliberately sought to remove themselves from institutional dependencies.1This interpretation of scholar-led publishing builds on an ever-emerging body of research, see e. g. Adema & Stone 2017, Adema & Moore 2017, Moore 2019, Adema & Moore 2021, and Fathallah, 2023 for a variety of examples from scholar-led book publishing, with analyses of the stakeholders’ underlying motivations.

From a diachronic perspective, there are a variety of factors that have played important parts in enabling scholar-led publishing’s drive towards independence over the years: technical affordances in digital publishing since the late 1990s/early 2000s such as the availability of content management systems – take, e.g. the popular blogging platform WordPress, and bespoke open-source solutions such as PKP’s Open Journal System and Open Monograph Press, and Lodel, plus a variety of newer digital platforms for publishing scholarly content such as Janeway, PubPub, Editoria, and Scalar, to name but a few – have enabled scholars to seize the means of scholarly production and run their own, independent scholar-led publishing ventures for both journals and the scholarly long-form (monographs, edited collections, etc.). Particularly in the context of book publishing, the technological affordance of Print on Demand cannot be overstated: Print on Demand’s wide-spread availability since the mid-2000s provided scholars with the means to not only publish long-form scholarship in digital form, but also make print books available themselves. As Paul Ashton, founder of re.press (launched in 2006) notes:

[Print on demand] allows equal entry for publishers into the whole book system regardless of size or power. I see this as possibly the most important thing that’s happened for publishing in the last 20 years; to some extent it is even as important as open-access models.

‘Interview with Paul Ashton’, Out of Ink

It also needs to be noted that for some presses, the drive towards independence has also been motivated by previous experiences made, e.g. when scholar-led presses had sought support from their universities but eventually learned that this support was either simply not available at their institution, or was tied to an understanding from the institution’s side (often in a US and/or UK context) that the new press should become self-sustaining or even generate profit for the university (see e.g. Ottina 2013, Adema & Stone 2017 & Interviews) – an institutional expectation that stood in direct opposition to the belief system and convictions of the scholars involved. Likewise, some scholar-led presses sought collaborations with libraries, with some of these remaining active to this day (as in the case of punctum’s collaboration with UCSB), while others have faded out over time (as in the case of Open Humanities Press).

Coming back to the issue of terminology, one can perceive vast differences in how these terms are used in different national contexts: take, for example, the US and UK, where most proponents seem to have settled on a general understanding of “community-led” publishing as representing the widest-possible, broad-stroke and “big tent” description of any kind of initiative that has its roots firmly in the academic community, in whatever shape or form, seeking to bring together the various sub-groups such as independent scholars, affiliated academics, library publishers, or scholarly associations, and hence focusing on inclusive academic communities that might seek to break free from large corporate publishers’ control.

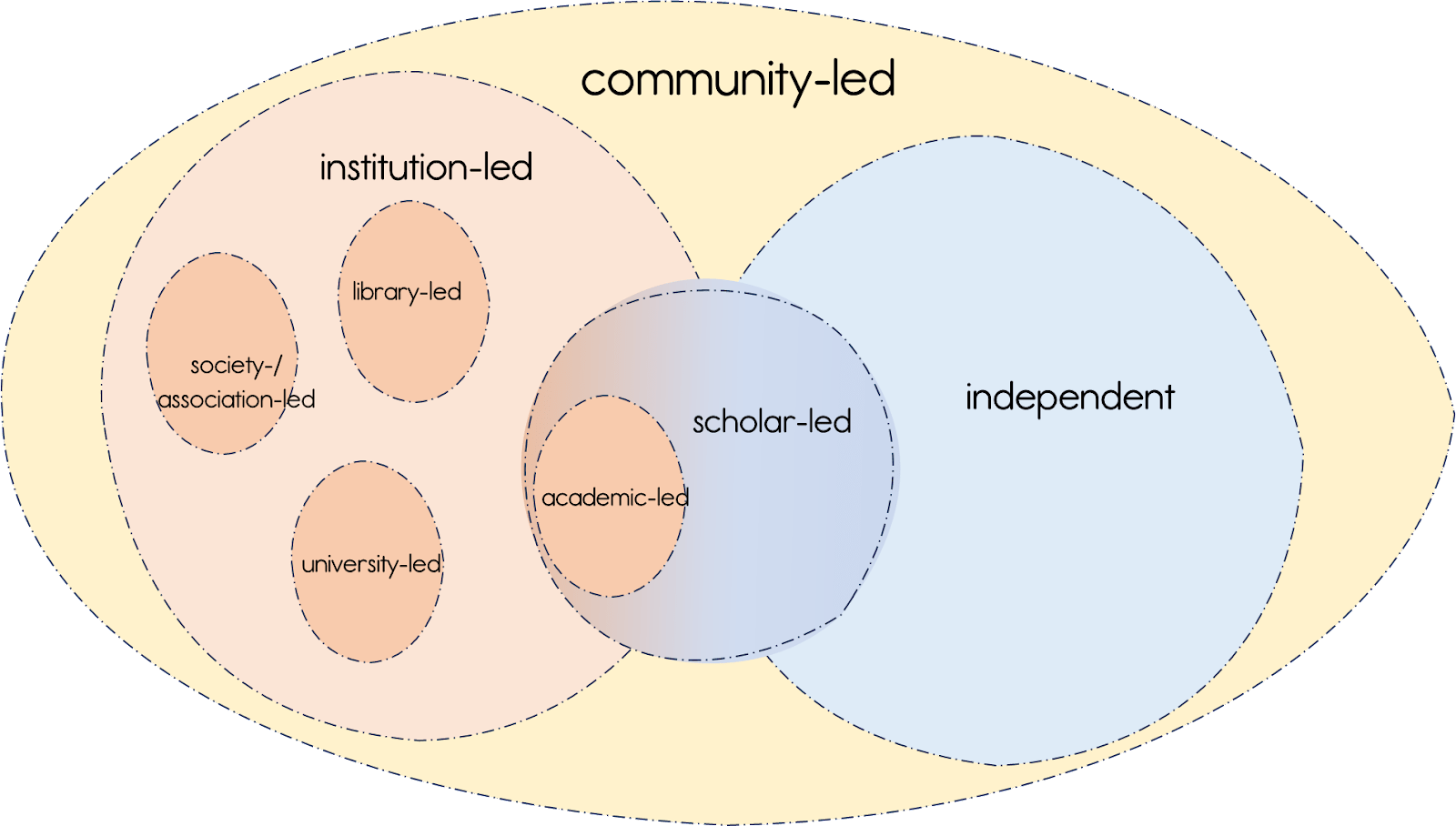

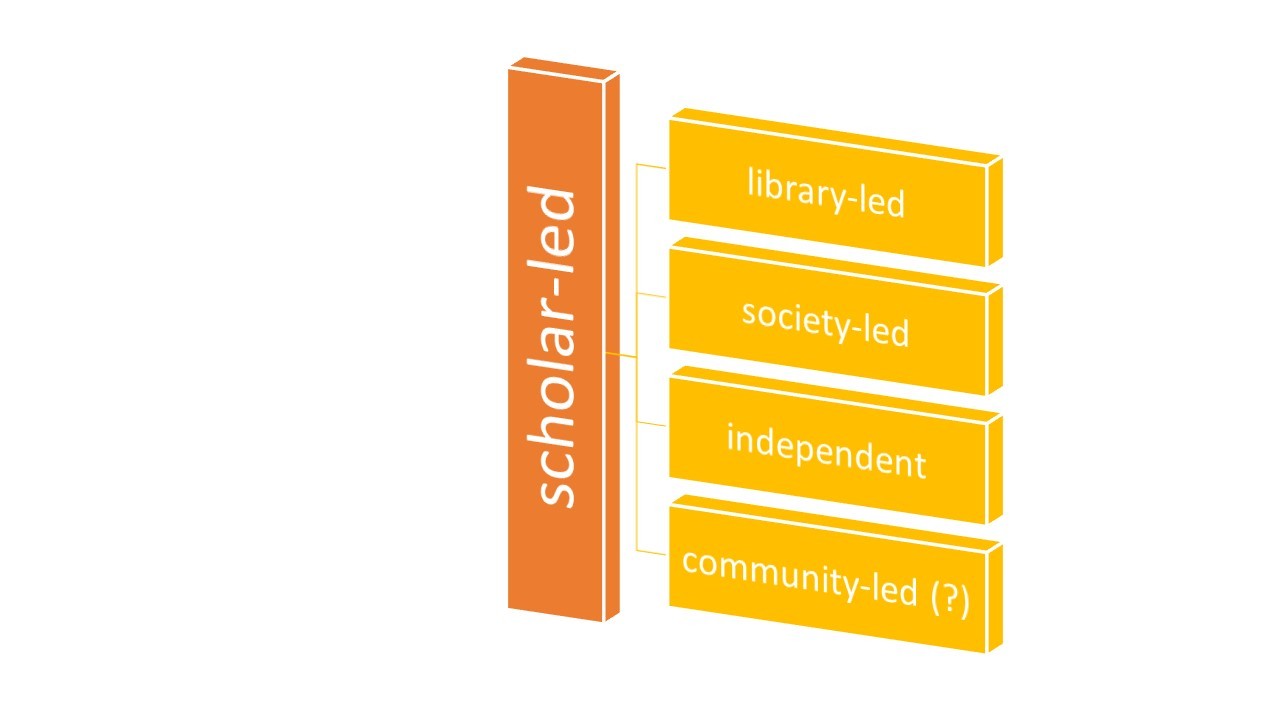

Looking at the terminology, in this interpretation shaped by UK/US discourse, one would then zoom in towards the more specific subsets of e.g. ‘library-‘, ‘academic-‘, ‘scholar-‘, or ‘association-led’ publishing, with an aim to highlight each subgroup’s more specific conditions, practices, and corresponding politics. Speaking from a linguistic perspective, one might hint at a semantic Hypernym-Hyperonym relation between ‘community-led’ publishing (as the Hypernym), and the more specific notions as the Hyperonyms. Or, to put it more plainly, ‘community-led’ publishing, in an English-speaking US/UK-focused connotation would be the broad-stroke umbrella term, under which more specific subgroups such as institution-led, library-led, university-led, society-led, or scholar-led approaches might be subsumed (see illustration of the different relationalities below).

All of this is further complicated by another sub-differentiation that exists in English between ‘academic’ and ‘scholar’ i.e. ‘academic’ signifying a researcher with an institutional affiliation and corresponding work contract, vs. ‘scholar’ = those who are engaging with scholarship more broadly, and independent from institutional affiliation, which can also include e.g. para-academics without formal links to a university, academics who have moved on to other professions, but still like to engage in research and scholarship on their own account, etc. This is why many scholars have started to adopt ‘scholar-led’ as a more inclusive adjective compared to ‘academic-led’ – and this was also the reason why the ScholarLed consortium decided to choose specifically this adjective as their name.

Adding yet another layer of complications to the terminological melange, there are German-language notions of publishing as being “wissenschaftsgeführt” or “wissenschaftsgeleitet”, which, in German discourse, appears to be taken to represent a conceptual closeness to the German reading of “scholar-led” publishing. On the other hand, it might be argued that the German terms’ literal translation might be construed to mean “led by academia”, i. e. by the academic community at large – ergo, in US/UK terminology, to “community-led” publishing (see also Schlosser & Mitchell 2019). Thus, where there appears to be, in German understanding, an assumption of synonymy between “community-led” and “scholar-led” approaches, US and UK colleagues understand these to be quite different from each other, as we have explored a few paragraphs earlier.

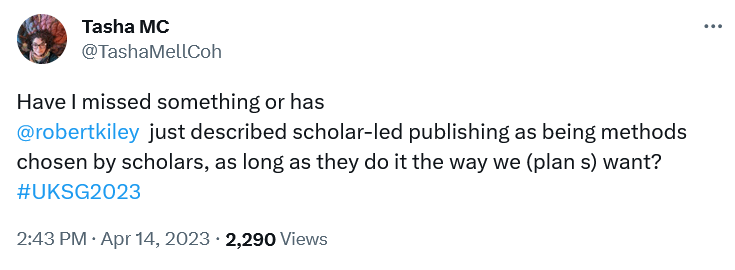

Now, while it might seem as if we are splitting metaphorical hairs here, the importance of what to call a thing becomes apparent when we consider that these differences of interpretation – particularly around the meaning of ‘scholar-led’ or ‘academic-led’ publishing – are now making waves at the very high level of European policymaking. Note, for example, the pan-European group of funders, Coalition S, who are seeking to “develop a more scholar-led research ecosystem”2See https://twitter.com/LizzieGadd/status/1646866476035452928, while appearing to describe scholar-led practices as needing to follow Plan S rules – which might seem surprising, given that scholar-led publishing, as understood in its original US/UK connotation, would be the one subgroup in the larger scholarly communications context that continues to question and break free from normative prescriptions from institutions or funders …

All in all, while the shift of focus towards Diamond OA and an implementation enacted together with, and for, the communities it serves is undoubtedly laudable, it seems pertinent to remind ourselves that the notion of ‘scholar-led’ can and should not serve as a catch-all or panacea to describe all kinds of initiatives led by a whole variety of stakeholders in the scholarly communications ecosystem seeking to break free from large commercial publishers.

A further note also needs to be added to highlight the fact that all of the adjectives listed here are usually understood only in a purely descriptive sense to specify and focus on certain groups in the larger publishing ecosystem, and do not per se touch on the rather different dimension of underlying value systems, i.e. values-led or -oriented approaches to publishing (which often appear to be implied in the former set of adjectives).

As has been argued above, scholar-led publishing points to a rather specific configuration within the larger publishing sphere that does exactly what it says on the tin: it focuses on scholars as the main actors and drivers behind a given publishing initiative. Or, as Sam Moore, with a focus on scholar-led monograph publishers, has noted previously on the ScholarLed blog:

Scholar-led publishers are just that, publishers led by scholars. I understand ‘scholars’ as broadly as possible, extending it to any actors who define their role as operating in a ‘scholarly’ capacity (library workers, independent scholars, etc.). ‘Led’, for me, is more specific and means managed by scholars, not just writing and editing the content, but the technical, practical and administrative sides to publishing too. Scholar-led projects comprise a mixture of the informal, the DIY and the spontaneous, alongside more professional publishing outlets like punctum books and Open Book Publishers (and everything in-between).

(2019)

Maybe to add a short interpretational addendum to the above, Sam’s mention of “operating in a scholarly capacity” for me points to a need to highlight the personal situatedness in which many practitioners in the scholarly communications ecosystem find themselves in: take, for example, many of our scholar-librarian colleagues who, by day, will represent their institution’s views in institution-led contexts and beyond, while they also, by night / in their freetime, choose to put on their scholar’s hat to engage in academic discourse that may be quite distinct from their day-to-day role and institutional employer’s position …

Differentiating between scholar-led and other approaches to publishing remains important because it helps to avoid glossing over the manifold organisational, legal, financial, and/or conceptual differences that exist between the various actors in the larger publishing ecosystem, and the corresponding politics that each group of actors bring to the table. Hence, one might deem it important to push back against any accidental conflation of these terms, which would practically de-value the specific context of each of the adjectives discussed here – publishing led and run by (independent) scholars is distinctly different from e.g. library-led, or association-led approaches … and all of these approaches would fall under the umbrella of community-led publishing. To refer back to Janneke Adema’s notion of messiness, yes, the publishing landscape remains messy – and we should develop and use language to describe different aspects of, and approaches to publishing in a meaningful way.

Hence, selecting “community-led” as the adjective of choice – as we have done, for example, with COPIM aka. Community-led Open Publication Infrastructures for Monographs – to describe an inclusive “big tent” approach that seeks to bring together a wide variety of actors from a diverse spectrum of backgrounds, disciplines, and academic contexts under one larger umbrella (be they from an institutional background such as library publishing, or from independent, scholar-led publishing initiatives such as the ScholarLed consortium, the initiatives represented in the Radical Open Access Collective, or any other independent community) seems preferable in the larger context of policy work, compared to risking accidental co-optation of an already-existing niche that is proud to remain independent.

References

Adema, J. (2014). Embracing Messiness: Open Access Offers the Chance to Creatively Experiment with Scholarly Publishing. Impact of Social Sciences (blog). https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2014/11/18/embracing-messiness-adema-pdsc14/.

Adema, J. (2017). Interview transcriptions : Changing Publishing Ecologies. A Landscape Study of New University Presses and Academic-led Publishing. Jisc. https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/6652/.

Adema, J., & Moore, S. A. (2017, October 27). The Radical Open Access Collective: Building alliances for a progressive, scholar-led commons. Impact of Social Sciences Blog. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/.

Adema, J., & Moore, S. A. (2021). Scaling Small; Or How to Envision New Relationalities for Knowledge Production. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.918.

Adema, J., & Stone, G. (2017). Changing Publishing Ecologies: A Landscape Study of New University Presses and Academic-Led Publishing. Jisc. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4420993.

Ashton, P. (2011). Interview with Paul Ashton, co-founder of re.press. Interview by Silvio Lorusso. Out of Ink | Future of the Publishing Industry. https://networkcultures.org/outofink/2011/09/13/interview-with-paul-ashton-co-founder-of-re-press/.

Fathallah, J. (2023). Governing Scholar-Led OA Book Publishers: Values, Practices, Barriers. https://doi.org/10.21428/785a6451.e6fcb523.

Moore, S. (2019). Common Struggles: Policy-based vs. scholar-led approaches to open access in the humanities. https://doi.org/10.17613/st5m-cx33.

Moore, S. (2019, October 24). Open *By* Whom? On the Meaning of ‘Scholar-Led’. ScholarLed Blog. https://blog.scholarled.org/on-the-meaning-of-scholar-led.

Ottina, D. (2013). From Sustainable Publishing To Resilient Communications. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society 11 (2): 604–13. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v11i2.528.

Schlosser, M., & Mitchell, C. (2019). Academy-Owned? Academic-Led? Community-Led? What’s at Stake in the Words We Use to Describe New Publishing Paradigms. Library Publishing Coalition. https://librarypublishing.org/alpd19-academy-owned-academic-led-community-led/.

Header image: Photo by Vardan Papikyan on Unsplash.

- 1This interpretation of scholar-led publishing builds on an ever-emerging body of research, see e. g. Adema & Stone 2017, Adema & Moore 2017, Moore 2019, Adema & Moore 2021, and Fathallah, 2023 for a variety of examples from scholar-led book publishing, with analyses of the stakeholders’ underlying motivations.

- 2

![]() Lost in translation? Revisiting notions of community- and scholar-led publishing in international contexts by Tobias Steiner is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Lost in translation? Revisiting notions of community- and scholar-led publishing in international contexts by Tobias Steiner is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.